A hero in the Madrid barrio of Vallecas, Agbonavbare's time between Rayo Vallecano's post symbolised a fight for equality and respect in Spanish football.

Header image: Jay Ashton

Those folk who travel to Madrid on holiday may be forgiven for not travelling down to the Vallecas neighbourhood. It doesn’t boast the grand boulevards of central Madrid, nor the architectural spark of other barrios (neighbourhoods) such as La Latina or Goya.

Vallecas, representing 400,000 people, has the highest rates of poverty, the lowest life expectancy, and wildest inequality of any of the Madrid barrios. These circumstances have created a cauldron for the growth of one of Spain’s most iconic football clubs.

Rayo Vallecano’s identity is built upon these radical roots. Constantly at odds with local government and the ownership, the fans make a point of fighting discrimination and fighting for the common person.

Try and attend a Rayo game and you may be confused why every match seems sold out online. In fact, there are no online methods for getting tickets. Fans need to go to the ticket office in person. Season ticket holders regularly camp for more than a day in the summer break to ensure they can attend games.

The main fan group at Rayo are Los Bukaneros (The pirates), formed in 1992. Matches in this era were full of racist chanting with groups like Real’s Ultras Sur, Atletico’s Frente Atletico, and Barcelona’s Boixos Nois being prominent forces in opposition to Los Bukaneros. Clubs were complicit in helping so-called ‘ultras’ attend games. Indeed, Ultras Sur were only banned from the Bernabeu in 2013.

In one famous incident, Valencia manager Guus Hiddink had to implore stadium security to remove a swastika flag from the stands in a match against Albacete in the 1991-92 season.

Los Bukaneros stood firmly against this. “In the early 1990s there was a small group of fans who copied the groups at Real and Atlético that had extreme right-wing ideologies,” says Rayo veteran Txus, who has been attending matches since 1991. “They disappeared quickly; there was no place for those ideas in Vallecas.”

This animosity was translated most clearly when Rayo visited the Santiago Bernabeu in the twilight of the 1992-93 season. Rayo had beaten Real Madrid 2-0 at the Estadio de Vallecas in the reverse match; Madrid knew they had to win to stay with a chance of winning the title. Rayo were battling at the bottom of the table to stay in the division.

However, the game was mired in racist abuse. The worst chants from Ultras Sur were directed at the Rayo goalkeeper, Nigerian Wilfred Agbonavbare.

Broadcast on television, fans (some young) were filmed chanting in favour of the Ku Klux Klan and hurling a barrage of well documented, distressing racial slurs at Agbonavbare.

Please be warned the below video contains distressing language.

During the match, Agbonavbare saved Michel’s penalty to earn a point for Rayo. Agbonavbare and the team’s performances over the two games arguably cost Madrid the title, and the three points (La Liga had two points for a win until 1995) Wilfred rescued were the difference between another season in La Liga or relegation.

These heroics amidst the disgusting abuse immediately endeared the quiet and unassuming goalkeeper with the Rayo faithful. It is easy to see why Agbonavbare is a cult hero at the Estadio de Vallecas, described as ‘the new idol in Vallecas’ by newspaper El Mundo Deportivo in 1992.

Born in Lagos on 5 October 1966, Agbonavbare went on to become the most capped foreign player to play for Rayo, until his record was beaten by Oscar Trejo in 2021. He helped Nigeria win the African Cup of Nations in 1994 and represented his nation at 1994 World Cup.

Though his wage was reportedly modest, enough to cover a small flat in the barrio, he was noted to be very personable and very friendly when out and about.

“He was a shy man, but he was always laughing,” says Andreu Idu, his agent. “He was happy in Vallecas.”

Indeed, Agbonavbare was known for his good sense of humour from day one, despite not speaking Spanish fluently when he arrived at Vallecano.

Former Spanish international Paco Jémez recalled Wilfred's voice and his humour. 'He struggled a bit with speaking Spanish. He had a very distinctive accent. He was a funny guy; when he spoke, between his accent and his quick wit, he was hilarious,' the coach said. They only shared a season together, but Jémez was captivated by the goalkeeper's personality. ‘Whenever we played Rayo, the first thing I did was go straight over to give Wilfred a hug,’ he added.

However, Agbonavbare's story outside of football was much more tragic. Without dedicated post-retirement support common of the era, Wilfred worked multiple jobs, such as working as a porter at Madrid’s airport, to be able to pay for his children’s education in Nigeria.

His wife passed away from breast cancer with a lot of his money going on her care before he himself was diagnosed with cancer. Once people were aware of his poor health, Los Bukaneros organised a fundraiser for his care, but it was too late. He died January 27, 2015. Visa problems prevented his children seeing him before his passing and could only attend his funeral.

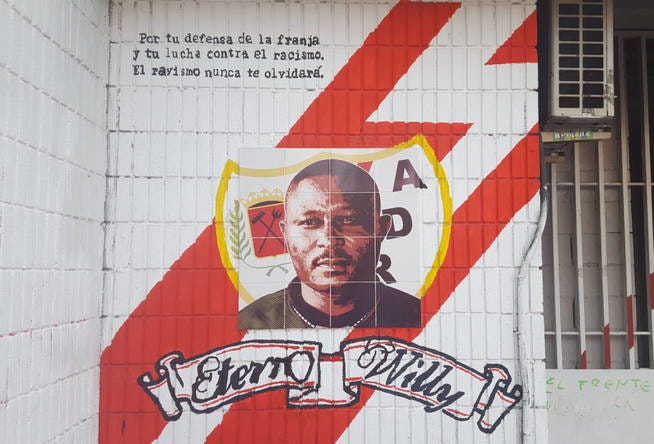

His legacy in Vallecas lives on, ever-present. Sports complexes are named after him, and his image is blazoned on many a lamp post. Gate 1 of Rayo’s stadium holds a mural dedicated to his memory. The inscription roughly reads ‘for your defence of the strip [shirt], and your fight against racism, Rayo will never forgot you.'

However, a battle between the ownership and fans threatens the ground Wilfred’s memory stands upon.

The Estadio de Vallecas itself has only three sides, with a brick wall occupying the space behind one of the goals. With a capacity of just 14,505 before the latest renovations, it is one of the smallest stadiums in any top division in Europe’s top five leagues, let alone in Spain.

Discussions are ongoing between Raúl Martin Presa, owner since 2011, and Madrid’s government to potentially move the club out of the barrio. A Madrid businessman, though by no means a successful one, Presa bought a club mired in debt for at most 1,000 euros. Constantly at odds with the Bukaneros, in 2021 his political affiliations strained tensions further after inviting VOX politicians Santiago Abascal and Rocío Monasterio as guests to the stadium’s executive seats.

VOX is a Spanish political party on the right wing of the political spectrum, which - in Abascal’s words - was formed as a reaction to the perceived failure of the Partido Popular (Spain’s mainstream conservative party) to uphold the values of the right. Naturally, this was at odds with Rayo’s fanbase.

Combined with the lack of investment, fans and the team have been pushed to breaking point.

“The training ground is in ruins, the fields are unplayable to the point that the first team refuses to train there for fear of injury, and the women’s team, which won the league several times not long ago, has been dismantled, leaving it in misery,” Txus said.

Although the latest compromise is to gently expand the capacity of the Estadio to 20,000, any increase beyond this is unfeasible for such a small plot of land nestled deep in the neighbourhood.

For the meantime at least, Agbonavbare’s mural as Rayo’s iconic goalkeeper will remain, standing as a testament to the depth of feeling amongst the Vallecas faithful towards both the goalkeeper and what he symbolised socially and politically.