A change in style often starts at the back. So, when the gaffer's time in charge comes to an end, one position can feel the burden more than others: the goalkeeper.

Autumn into early winter marks a transitional time of year, when everything feels in flux. The leaves are turning, darkness creeps into longer and longer stretches of our waking lives, and time itself has been rolled back to account for the general sense of upheaval.

This state of change is mirrored in the footballing world too. Sleeves lengthen, snoods start whispering to tricky wingers like the Green Goblin’s mask, and the highlighter-yellow match balls start to whizz off production lines. It’s also ‘sacking season’ - that time of year when chairmen panic, agents whisper, and ‘mutual consent’ becomes the sport’s most misused euphemism.

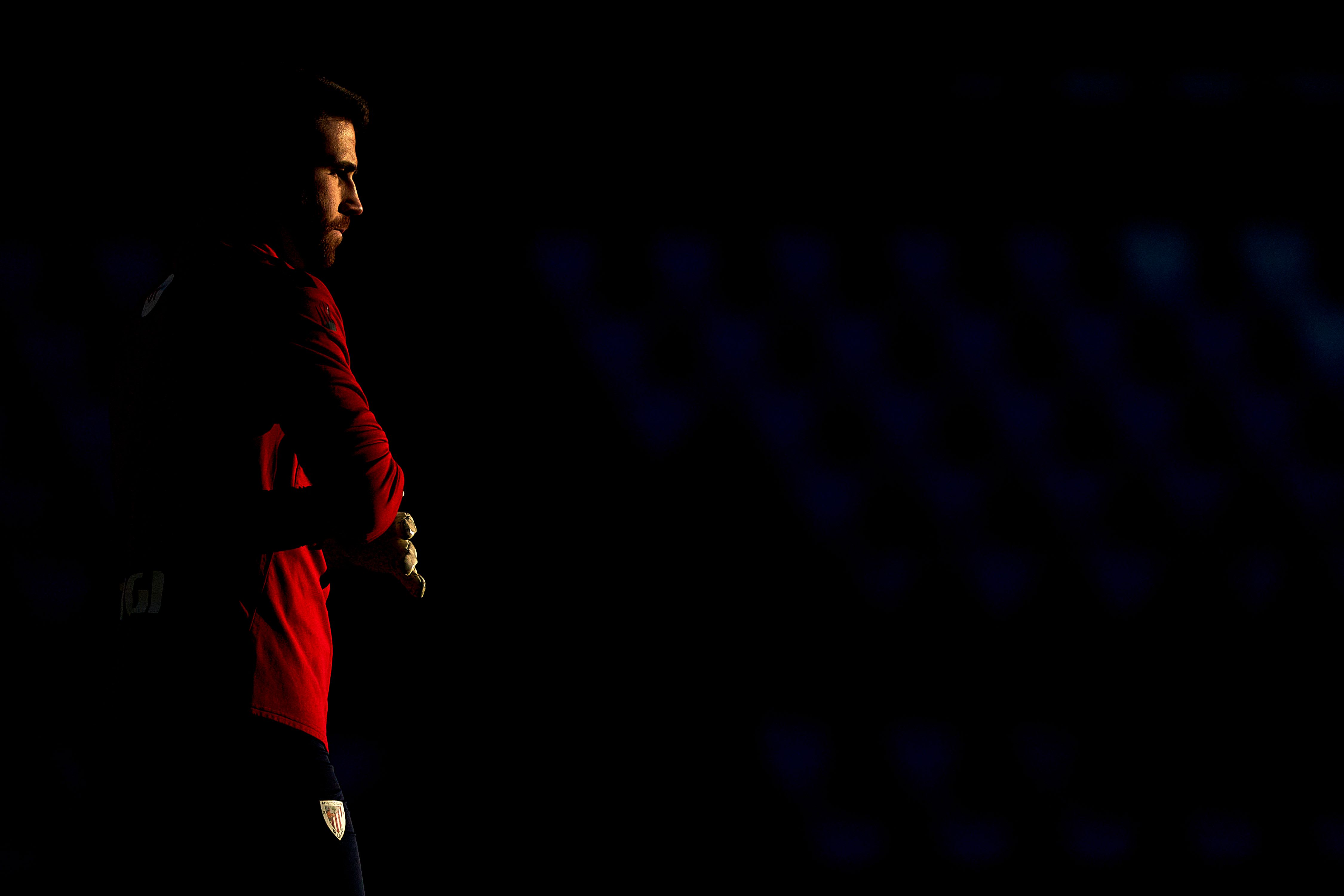

For most players, a managerial change signals a clean slate. A chance to impress a new boss, show adaptability, or reinvent yourself. For goalkeepers, it’s something closer to roulette. Unlike outfield players, keepers live and die by trust, and trust is not a commodity easily transferred to new managers.

Every manager has their goalkeeper. Someone who fits their philosophy, temperament, and need for control. The relationship between the two isn’t tactical so much as psychological, a manager sees something of himself in his number one.

Pep Guardiola wanted a goalkeeper who could think like a midfielder. Claudio Bravo replaced Joe Hart almost overnight, not because Hart couldn’t save, but because he couldn’t play. For Pep, it all starts at the back.

José Mourinho demands loyalty and command. Petr Čech at Chelsea, Julio César at Inter, Rui Patrício at Roma - each an extension of his authority, lieutenants who saw the game through his eyes.

Carlo Ancelotti, meanwhile, prefers calm hands and quiet authority. Think Thibaut Courtois at Madrid or Dida at Milan - steady, unflappable, allergic to drama. The kind of goalkeeper who never needs to shout to be listened to.

Every one of them tells you something about the man in the dugout. Managers project their ideals onto the person between the posts. So when a manager goes, the goalkeeper often becomes a legacy issue, a last fingerprint of the old regime.

The incoming coach brings a new gospel. A different shape, a louder dressing room, or a new way to build from the back - and sometimes all three. The old partisan goalkeeper coach has followed his mate out the door, and suddenly the new man wants someone who kicks better, shouts louder, or simply looks more like his kind of player. In that moment, the goalkeeper may no longer be a constant, but a question mark.

At the time of writing, four permanent managers have already been sacked in the Premier League this season, and more often than not, when the guillotine falls on the dugout, the goalkeeper’s head is next.

Chelsea are the clearest example. Since the start of 2023 they have cycled through four managers, and with each new ideology has come a new No. 1. Kepa Arrizabalaga, Édouard Mendy, Robert Sánchez, Djordje Petrović, and then back to Sanchez. A revolving door of gloves. It shows, more clearly than anywhere, how a goalkeeper can be an inheritance, not a certainty.

When a new gaffer wants to put his stamp on a team, and a clear philosophy shift walks through the door, the root of change often starts between the posts. Managers have increasingly realised how a goalkeeper's tactical and technical match to a coaching vision is foundational to the functioning of any new style.

André Onana's move to Manchester United embodied the modern ‘philosophy goalkeeper’ signing. He was essential to Erik ten Hag’s build-up, yet exposed the moment the structure around him wobbled. United’s autumn 2024 slump - 19 goals conceded in 12 league games - dragged his confidence with it. When Amorim arrived, he wanted reassurance rather than risk. Senne Lammens stepped in; Onana was pushed aside. The vision changed, so the goalkeeper changed too.

The tremors reach everywhere. Burnley’s James Trafford received his big break, and was then benched three games after Vincent Kompany left. At Crystal Palace, Dean Henderson waited on the bench while the club searched for direction, returning only through injury rather than conviction.

Goalkeepers, already isolated and scrutinised for every mistake, feel that pressure magnified with each new manager. New routines, new coaches, new communication lines: all chip away at composure, leaving them vulnerable not just on the ball, but in the mind. Career longevity can shrink under the weight of repeated upheaval.

As Ben Foster put it, ‘You spend two months learning a new manager’s philosophy, then they’re gone.’ For a goalkeeper, it’s more than a technical reset; it’s an emotional aftershock, shaking the foundations of trust, instinct, and rhythm.

But then those are the decisions a new manager is paid to make. Specialist coaching counsel can help, but as former Leeds and Reading boss Brian McDermott told Goalkeeper.com, "it's about what happens on the pitch. So that doesn't really change. It's not what someone else says to me, it's what I see.”

This is not coincidence. It is the physics of instability. Has the number one shirt ever felt more fragile?

One is reminded of one of football's fringe debates. Should goalkeepers be treated a little more like outfielders? When a player on the park underperforms, they're hooked in favour of a substitute. When starting elevens rotate, the goalkeeper tends to remain on the bench. If the goalkeeper is as foundational as managerial changes often emphasise, then shouldn't we see this fragility in practice more often?

Mikel Arteta made headlines a few years ago when he boldly claimed he'd considered switching goalkeepers half way through a game. 'Someone is going to do it, and maybe [people will say] that's strange. But why not? Tell me why not. You have all the qualities in another goalkeeper to do something, you want to change the momentum, do it', explained Arteta.

‘I want Aaron [Ramsdale] to react the same as Gabriel Jesus. The same as Kai Havertz, as Takehiro Tomiyasu. Exactly the same. We play with 11 players, not 10 plus one.’

Modern football has made the goalkeeper’s role more precarious than ever. Managers now demand goalkeepers who can play, pass, and press as much as they save. A mid-season managerial change does not just swap personnel. It rewrites the position’s internal logic.

A goalkeeper trained as a sweeper suddenly finds himself marooned in the six-yard box under a conservative boss. The same player who once completed 60 passes per game may now be ordered to launch it long and safe. What was once positional bravery becomes reckless wandering.

It’s the tactical equivalent of changing instruments mid-song. The melody is familiar, but the notes no longer fit. And, the instability isn’t confined to the men’s game. Women’s football has entered its own era of managerial churn. Emma Hayes’ departure from Chelsea in 2024, Jonatan Giráldez leaving Barcelona, and Sonia Bompastor moving on from Lyon all disrupted finely tuned goalkeeping systems built around distribution and possession. The women’s game has evolved fast, goalkeepers are no longer just shot-stoppers, but integral to build-up play, making them especially vulnerable to philosophical resets.

And with the new eight-second rule, penalising keepers for holding the ball too long, the tempo is merciless. Managers who favour slower build-up now risk an enforced turnover, while keepers accustomed to rapid transitions find themselves punished for instinct.

Adapt or vanish.

The FA’s 2024 coaching report confirms what every goalkeeper already senses. At clubs seeing two or more managerial changes per season, stress spikes sharply and confidence drops noticeably.

Sports psychology research backs it up: managerial changes are ‘significant occupational stressors’ that heighten anxiety, disrupt concentration, and increase injury risk. Goalkeepers, already prone to higher rates of depression than outfield players, feel the impact most acutely. And when a new manager tweaks physical training loads, soft-tissue injuries spike - one of the more invisible impacts of sacking season.

Managers increasingly include ‘underperformance clauses’ to safeguard their own payouts. Goalkeepers rarely enjoy the same protection. Drop form, lose the manager’s trust, and suddenly you’re stripped of bonuses, status, or even the shirt - sometimes permanently.

Some goalkeepers, however, have learned to turn misfortune into strategy. The loan market, once seen as exile, is now a survival tool. Young goalkeepers dropped after a managerial change often move temporarily, rebuild confidence, and return sharper. It’s football’s new adaptation loop: evolve elsewhere, return stronger, and hope the next round of chaos doesn’t undo the work.

Indeed, sometimes a change in managerial relationship can be the tonic a young goalkeeper needs to keep moving in the right direction. Speaking to Goalkeeper.com whilst at Leyton Orient, now-Swansea number one Lawrence Vigouroux admitted how when he moved to Swindon Town early in his career, then-boss Richie Wellens set the goalkeeper on the straight and narrow.

“I always will love Swindon,” he said. “As a young lad trying to make a way in the game, they gave me an opportunity to play week in week out. I kind of took the mick a little bit in terms of my lifestyle and I thought I would play every week. When Richie came into Swindon, he was honest with me, he said my lifestyle wasn't right, I didn't live the right way, my attitude wasn't good enough.”

When the two reunited at Leyton Orient, Vigouroux explained how “he came in, we had a chat and I always said to him that I'm a different man now. Our relationship [grew] to a place where I can speak to him about anything and I see him as a really good manager, an unbelievable coach, but also as someone that I have a lot of respect for and really enjoy working under.”

But the managerial merry-go-round remains football’s annual ritual of chaos. For goalkeepers, it’s also a trial of identity. They’re not just defending the goal anymore; they’re defending their philosophy, their reputation, and their future every time a club decides to hit reset.

When trust can vanish as quickly as a clean sheet, the real save is made in the mind. Each season, the pitch tilts underfoot. The dugout falls away. The bench grows colder. The boardroom catches fire. The entire football world whirls off its axis again and again. In the center of that storm, all a goalkeeper can do is hold on, stay still inside himself, and hope that both his hands and his head stay true.